Chilean money.

I returned to Peru 130 years too late, and found it to be Chile.

Once famous for its flourishing copper and saltpeter mines, the northern province of Chile was wrested from Peru during the War Of The Pacific in 1879. Nowadays, it's a dry and barren region peppered with creaking ghost towns--eerie, abandoned settlements that were once Chilean mining hubs.

The War Of The Pacific also saw Chile plunge headlong into fiat currency, with the government printing more and more money to make up for the rising cost of war. This led to serious inflation, a problem Chile has been wrestling with in one way or another throughout much of its history.

Currently Chile is a prosperous country, with Western prices and a cosmopolitan feel. It's a stark contrast to poor neighbouring Bolivia, full of ragged buildings and pot-holed roads.

Which is why it feels so strange that one Chilean peso is worth 0.01 of a borderline worthless Boliviano.

***

Iquique, caught in between surf and sand.

There's something quite unsettling about going to a cash machine, and withdrawing 70,000 of a currency.

In Chile, zeroes are important--a razor will set you back 500 pesos, a box of breakfast cereal 1,600. (And alarmingly, many supermarkets use the "$" sign for pesos, making prices perilously easy to confuse with dollars. ) In an effort to make costs seem more sensible, some shops substitute the comma in each "1,000" or "10,000" for a decimal point, like so: "10.000." But there are still zeroes everywhere, like multiplying rabbits.

Upon arriving in Chile, I stopped off at Iquique--a bustling port city located between the ocean and a vast sand dune named Cerro Dragon. Beloved by surfers, Iquique was famously visited by Charles Darwin in 1835, who described it as: "Very much in want of everyday necessities, such as water and firewood."

Nowadays, Iquique is home to the Zofri; a vast Duty-free mall, crammed with discount goods and overpriced ice cream. It's a monument to capitalism worthy of the USA, and it sits in one of the city's most ramshackle-looking neighbourhoods.

Darwin thought Iquique was empty. Now it's home to all the goods that money can buy.

***

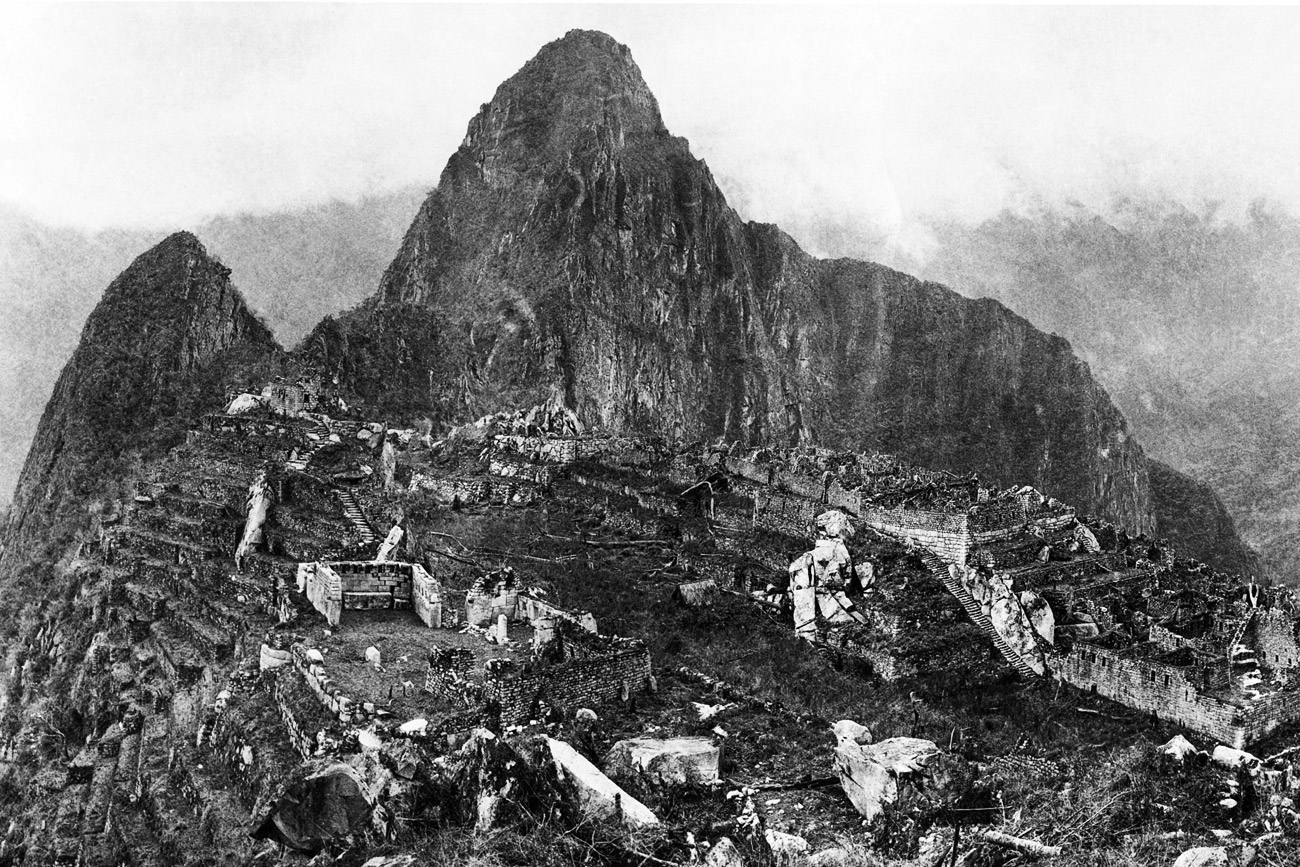

Humberstone, an abandoned Chilean mining town.

Money is a silly thing, when you think about it.

Originally designed as a means of exchanging shiny beads for goats, it has since become the mechanism by which a mindbogglingly complicated global infrastructure works. And yet, as Chile's tumultuous history shows, there is no safety with money. Economic models can be overturned at the slightest revolution.

In 1973, Chile's the then-new Pinochet regime brought in the Chicago Boys--a group of neoliberal economists educated in the USA, tasked with redesigning Chile's formerly socialist economy. This resulted in a crazed orgy of free-market restructuring, and debate still rages among academics as to whether the Chicago Boy reforms were responsible for Chile's devastating economic Crisis (note the capitalisation) in 1982.

Nowadays, Chile is one of the most prosperous and stable economies in Latin America, but the peso shows no sign of deflating to less outragious levels. Consequently and curiously, Chileans have effortlessly achieved what so many Brits and North Americans struggle and strive for.

Everyone's a millionaire.

If only a million was worth a little more.

EXTRA BITS:

>The City of Iquique, home to the Zofri, caught between sea and sand in the shadow of the mighty Cerro Dragon.

The more travel, the more I find--everywhere's a fantasy, if you phrase it right.