Let's talk about The Big Bang.

No, not that one. I mean The Big Bang Young Scientists & Engineers Fair – one of the largest science celebrations in the UK.

Held in the Birmingham NEC – a cavernous space that resembles a cross between an aircraft hangar and a shopping mall – it’s an explosive cavalcade of technology, science, maths and engineering.

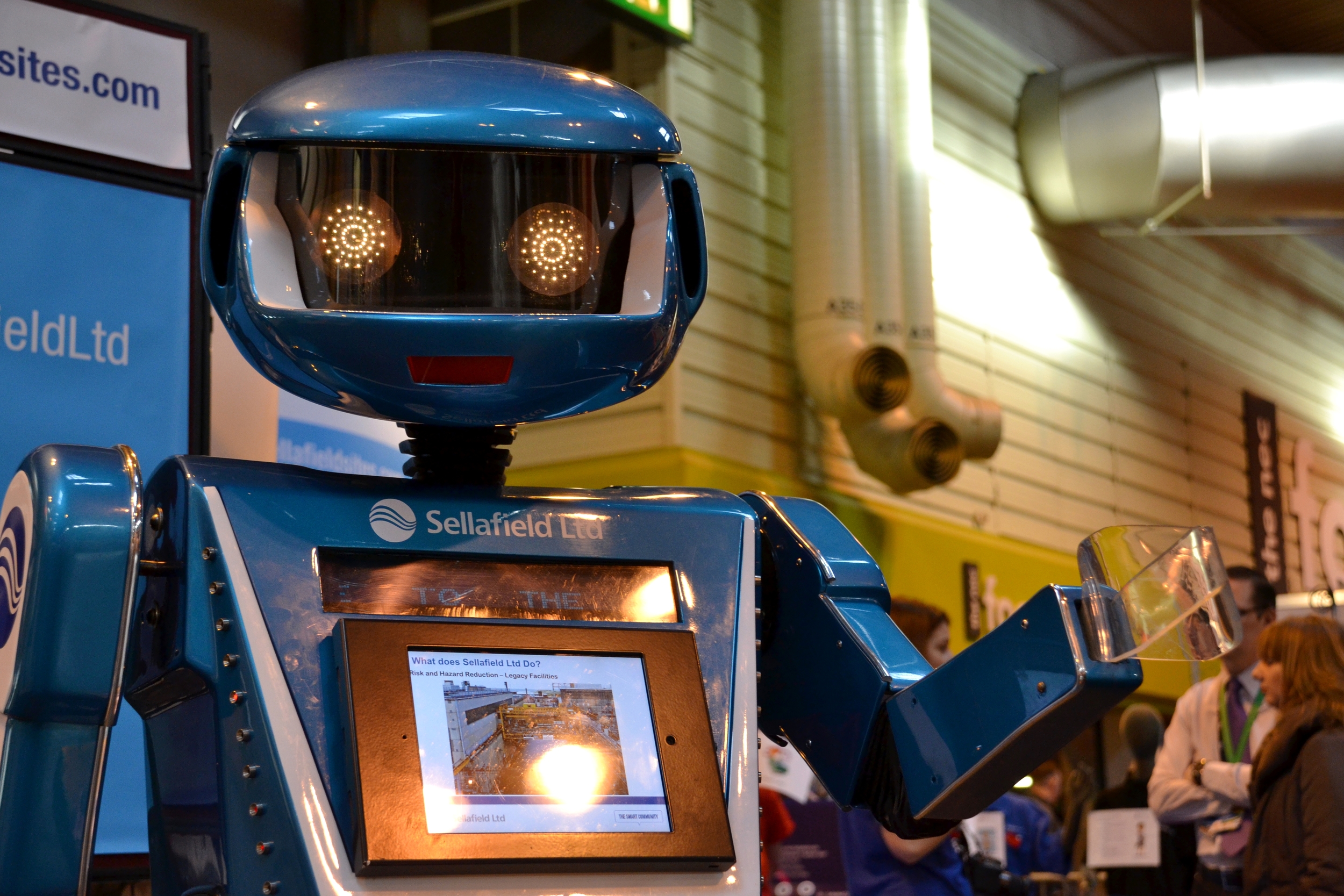

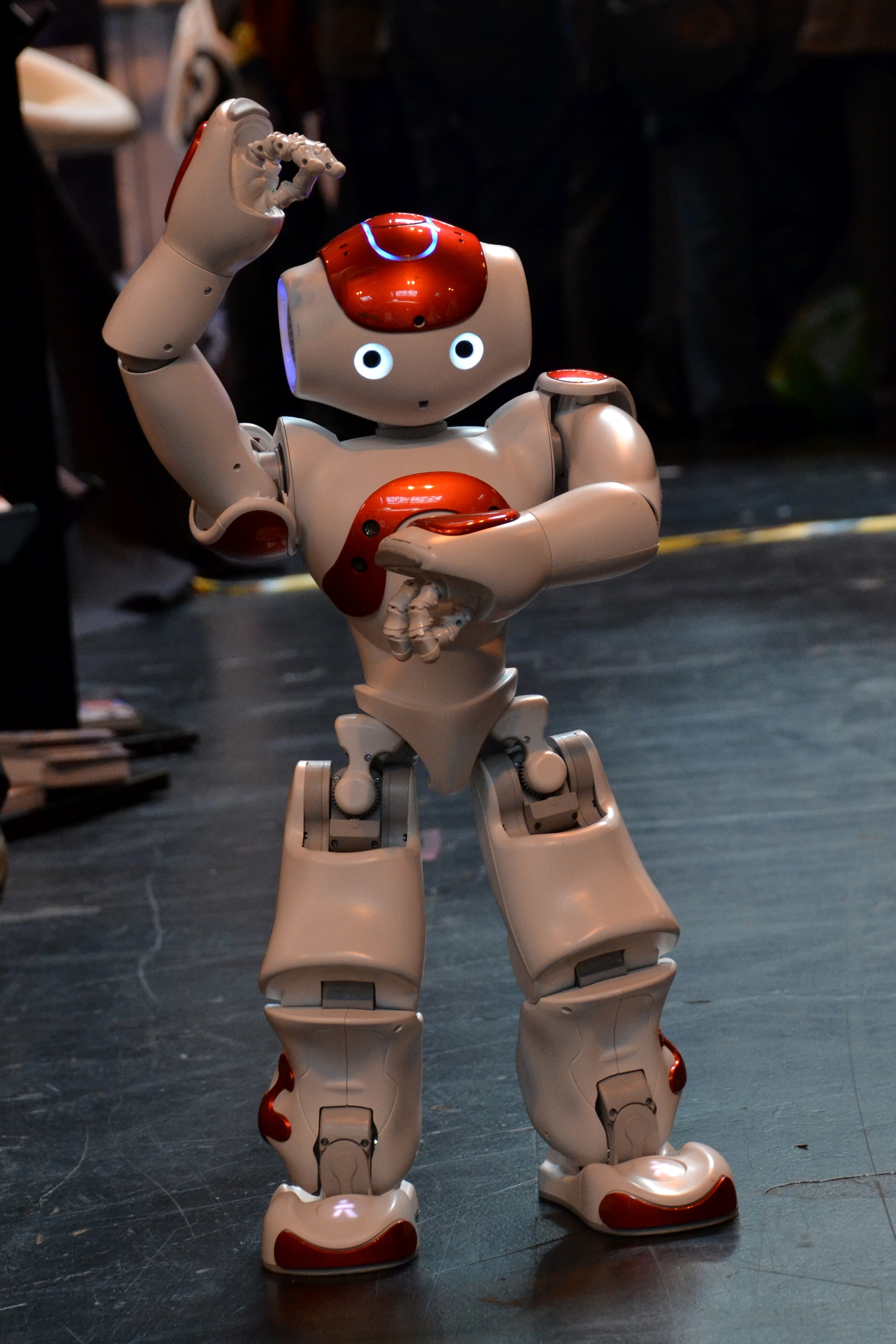

Every year, thousands of children from all over Great Britain come crashing through the Fair, dragging tired teachers behind them, jumping up and down as they sample exhibition stalls covered with robots, magnets, VR helmets, and all sorts of other shiny toys to play with.

As one of many volunteers who helped run the 2016 Big Bang Fair, I have to say, I found the swarming children rather inconvenient.

I wanted to play with the robots.

***

***

The word “scientist” was first coined in the year 1834 by William Whewell – reverend, philosopher and Master of Trinity College, Cambridge. After agonising for some time over what to call folk of scientific inquiry (hitherto known as “natural philosophers,”) he chose “scientist” as a logical extension of the word “artist.”

If a person who does art is an artist, Whewall reasoned, then a person who does science must be a scientist (the word “science” is actually much older than “scientist,” dating back to the 14th century).

It’s appropriate, I think, that the word “scientist” derives from “artist.” After all, no matter how rigorous the scientific process applied, things always start with a creative spark.

***

***

The main draw of The Big Bang Fair is its awards.

Children from age 11 to 18 are invited to bring their own personal science projects to the fair, where they’re examined by judges. A lucky few will win prized titles like UK Young Scientist of the Year.

While waiting for the robots to free up, I perused a few of these projects.

I met a group of teenage boys who had designed a disability-friendly hot rod, then built it by themselves from scratch.

I spoke to a teenage girl who had made an oil-based UV sun-blocker, and turned her phone into an improvised UV-light to demonstrate it.

I was awed by a 15 year-old prodigy named Krtin Nithiyanandam, who had taken some time out from being a teenager to create a new early-stage detection method for Alzheimer’s.

Never mind creative sparks. Kids like that have wildfire talent.

***

***

Unfortunately, in the current austerity climate, events like The Big Bang Fair are increasingly in danger of being regarded as expendable luxuries. They’re not. They’re essential, and not just because they provide lots of shiny toys to play with.

They’re where tomorrow’s scientists come from. More crucially, they’re where tomorrow’s scientists discover that imagination gets results. That science thrives on creativity as well as solid process. And that sometimes, it pays to be able to redesign the box.

They’re where the future learns to happen.

And most importantly, they’re where I get to play with robots.

EXTRA BITS:

>The first use of the word "scientist" was in Whewell's 1834 review of a book by Scottish science writer and polymath Mary Sommerville. In this review, Whewell makes a vaguely progressive if rather muddled attempt to talk about women in science, calling Sommerville "One of the brightest ornaments in England."

>Meanwhile, in the 21st century, this year's Big Bang Fair seemed gratifyingly interested in tackling the issue of women in STEM fields, with with groups like the STEMettes roving the floor.

>I got the opportunity to volunteer at The Big Bang Fair because I'm on the mailing list of the British Science Association. Check them out; they do good work.

>For more information on The Big Bang Fair, see here.